The nation needs to establish a national challenge grant program for innovation and reframe the role of research universities

By Robert Birgeneau, Chancellor Emeritus of the University of California, Berkeley

Explore Keywords

competitiveness

funding grants

human capital

Science, the Endless Frontier

knowledge-based

leaders aid

research science

Vannevar Bush

Carnegie

endowment aid

funding investment

grants

Morrill Act

risk-taking scholarships

endowment

grants investment

Science, the Endless Frontier

Morrill Act

Truman Commission

Vannevar Bush

Science, the Endless Frontier

competitiveness funding

governance

research

grants information

Master Plan risk-taking

science teaching

aid debt

funding governance

Truman Commission

investment loans

Morrill Act

scholarships

competitiveness

funding aid grants

human capital

Vannevar Bush

knowledge-based

leaders research science

Science, the Endless Frontier

©Nick White/Digitalvision/Thinkstock

That is the good news. Unfortunately, the bad news is that this record of excellence and achievement may not continue to hold up—and if it does not, we may find ourselves losing our position as worldwide leaders. The interconnected economies of most nations are fueled by knowledge and innovation, and much of that intellectual energy is born and nourished in our great research universities.

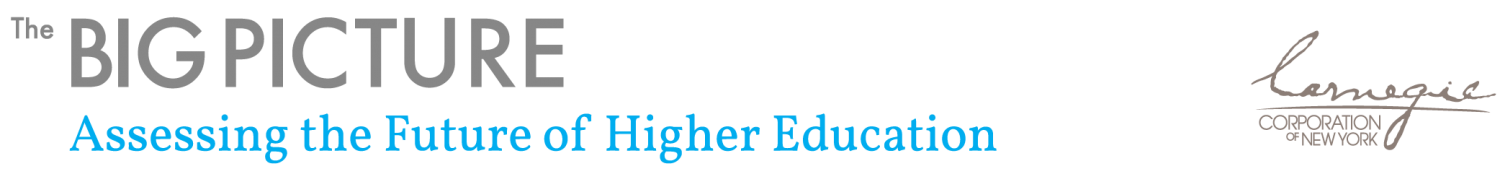

Today, these American institutions are facing unprecedented challenges, in large part because of the 2008 financial meltdown, as well as the ongoing, long-term decline in state support. Policymakers and the public expect our universities to continue to be accessible to all qualified students and at the same time to produce, achieve, and maintain excellence. However, state funding for U.S. universities has plummeted—at the University of California, Berkeley, for example, from which I recently stepped down after nine years as chancellor, funding has dropped from 47 percent of overall budgets in 1991 to 10 percent today.

We cannot afford to make mistakes in our support for higher education and research and so ought to collaborate and learn from one another in this domain.

Many of our sister institutions across the nation have gone from being state-supported to state-assisted to, at best, state-located. As a result of this progressive state disinvestment, public research and teaching universities have seen tuitions increase dramatically, professors furloughed, classes grow steadily larger, and infrastructures deteriorate. If the current trend persists, the result will be extremely damaging to our higher education enterprise, especially the public-university sector.

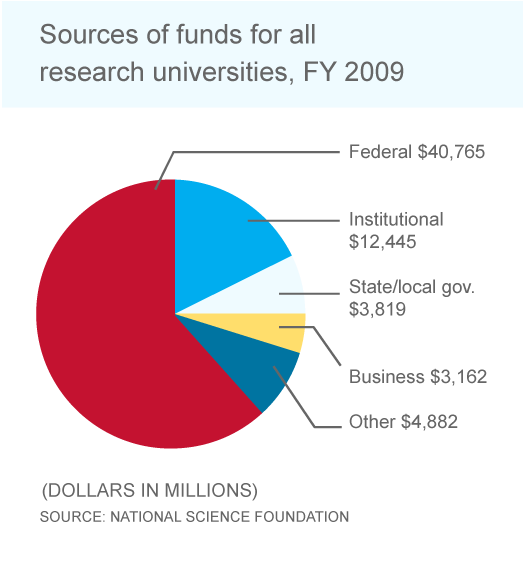

The United States is the only advanced country in which the federal government does not contribute directly to the financing of the educational operations of its top universities. However, it is clearly in our national interest that public research and teaching universities thrive in every state, that they are fully accessible, and that students graduate with minimal debt.

In previous eras, the United States responded to challenges by expanding higher education and bolstering its capacity to serve the country. In 1862, in the midst of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Act, granting federal land to help states establish public colleges. In 1944, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the GI Bill and commissioned the eminent scientist Vannevar Bush to craft a comprehensive science policy for the nation. The following year, Bush presented to Harry Truman the seminal report “Science, the Endless Frontier,” which argued that the nation’s universities were best suited to take the lead in conducting basic research. The policy Bush recommended still guides America’s scientific enterprise. In 1946, Truman authorized a commission on higher education that led to the development of community colleges, and in 1965, Lyndon Johnson signed the Higher Education Act to launch the first major student aid program.

In previous eras, the United States responded to challenges by expanding higher education and bolstering its capacity to serve the country. In 1862, in the midst of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Act, granting federal land to help states establish public colleges. In 1944, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the GI Bill and commissioned the eminent scientist Vannevar Bush to craft a comprehensive science policy for the nation. The following year, Bush presented to Harry Truman the seminal report “Science, the Endless Frontier,” which argued that the nation’s universities were best suited to take the lead in conducting basic research. The policy Bush recommended still guides America’s scientific enterprise. In 1946, Truman authorized a commission on higher education that led to the development of community colleges, and in 1965, Lyndon Johnson signed the Higher Education Act to launch the first major student aid program.

Today, our situation calls for a similarly dramatic response that will bring the federal government, states, research institutions, and philanthropic organizations into an unprecedented public-private partnership for innovation.

Under one such program proposed by us at Berkeley:

■ Over a 10-year period, 100 of our nation’s best public research universities would work with private philanthropies and corporations to raise new permanent endowed capital.

■ The federal government would provide $1 billion annually for 10 years in challenge grants to match fully a number of new philanthropic investments in university endowments for research and teaching. This would supplement the government’s current funding commitments for university-based research.

■ Each state would match the federal contribution over the decade according to a formula to be determined—say, one to one—and as a condition of receiving the federal and philanthropic funds, the state governments would promise, at a minimum, to continue funding their universities at the same level and agree not to substitute federal funding for that currently supplied by the state.

The grants would be available to top research and teaching universities in all states and distributed based on population and competition. Of course, these grants would carry safeguards to ensure both equitable distribution and state fiscal responsibility. For example, the federal government would require that state institutions demonstrate a commitment to college access for a diverse population of students, redouble efforts to keep costs down, preserve a balance between research and teaching, and optimize graduation and retention rates. Moreover, the new endowments would be structured and governed to protect institutional integrity, as well as autonomy and academic freedom.

One proven way to spur this challenge grant initiative would be to establish a high-level national commission to engage the public will and lay out a roadmap for success. Such a commission, much like the work of Vannevar Bush and the Truman Commission after World War II, could examine the place of the research university and consider questions central to the basic research and educational agendas. Preparation for this is already under way through a study sponsored by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences appropriately named “The Lincoln Project.”

The commission could address other crucial issues, including: What is the appropriate balance among the research, teaching, and public service missions of universities? How can we help faculty members keep pace with their digitally adept students and use technology to enhance learning? How do we ensure that all segments of our diverse population have equal access to these great institutions? How should universities respond to forces such as commercialization that could threaten academic integrity?

The solutions we seek must be pragmatic yet ambitious. We must look beyond mere sustainability so that our research and teaching universities—and our nation—will thrive for generations.